About

The commons exists, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Into the cave

Every system in which people act together; from teams and institutions to online platforms and global networks, relies on conditions that make cooperation possible. These conditions are rarely named, rarely measured, and rarely discussed directly. But when they weaken, the effects are immediate: confusion increases, friction rises, and control expands.

When coordination becomes difficult, most systems respond by adding structure from above: more process, more oversight, more rules. This response is understandable. Control is visible. It produces motion. But motion is not the same as cooperation, and over time control becomes expensive and increasingly ineffective.

Cooperation is different. It is not a moral quality or a personal trait. It is a structural phenomenon: the alignment of shared meaning and reciprocal contribution, sustained by visible activity and meaningful commitments. When these conditions reinforce one another, systems remain adaptive. When they degrade, systems harden. They defend rather than learn.

The framework does not tell anyone what to do. [It] makes visible the structural conditions that systems already depend on, and the predictable ways those conditions fail.

These dynamics are familiar. They appear in strained teams, in institutions unable to adjust to new realities, in political environments where interpretation fractures faster than it can stabilise, and in online spaces where meaning and coordination are concentrated at unprecedented scale. They are also present in everyday work, where people are asked to cooperate under conditions that feel increasingly fragile.

Despite this, cooperation itself often remains invisible. Its successes are attributed to culture or personality; its failures to individual behaviour. Without a way to describe how cooperation actually functions, systems default to the most tangible tool available: control.

My work began as an attempt to understand this invisibility.

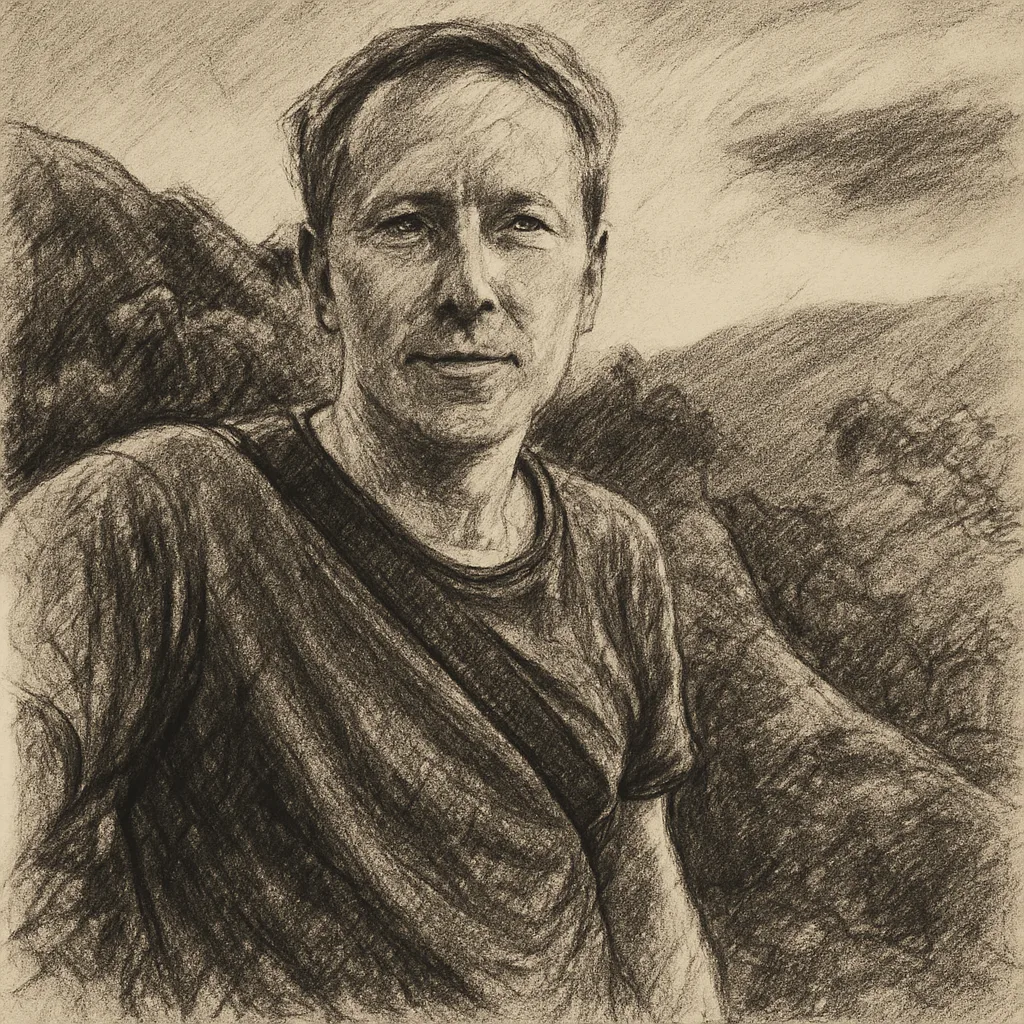

Mike Harris – Founder of Exonym

What made this period difficult was not misunderstanding by others, but my own inability to articulate what I was observing.

Long before the framework had a name, I encountered systems that behaved in ways I could sense but could not yet explain. Systems that were cooperative for a time, then degraded, and later—sometimes unexpectedly—became cooperative again. What stood out was not intention, but structure.

I first encountered this pattern in quality assurance, where coordination is typically framed through process and compliance. The assumption is simple: if the rules are right and followed correctly, outcomes will follow. Over time, it became clear how rigid process reshapes the work beneath it; by flattening judgment, distorting behaviour, and turning procedure into a proxy for responsibility. None of this required bad actors. It emerged naturally from the available tools.

Around the same time, large technology platforms were expanding rapidly. This made another structural issue visible: meaning, identity, and coordination were being centralised at a scale no existing institution was designed to handle. This was not primarily a question of founders or intent, but of feedback collapse under concentration.

Governments weren’t resisting it; they were seeking it. That moment pushed me toward the deeper problem of identity. Toward how identity systems and their structural effects. How they create hierarchy, collapse feedback loops, and make cooperation fragile.

Across these contexts, the same question kept returning: How does order emerge without rising above the people inside it?

Systems like money, social media, identity, and governance often have a tendency to dominate the people who rely on them. Over time, I explored whether systems could be structured in ways that remained responsive rather than dominating. I experimented, revised, and often discarded designs that were elegant but wrong.

Much of this work involved uncertainty. I understood behaviour long before I understood structure. Many iterations failed. Others almost worked. Progress was slow, and clarity came late.

What made this period difficult was not misunderstanding by others, but my own inability to articulate what I was observing. I was aware of the effects, but not yet of the structure producing them.

Only later did a clearer pattern emerge.

Out of the cave

The Generative Commons is an articulation of that pattern: the observation that cooperation has a structure, and that this structure explains both its persistence and its collapse.

The framework describes how shared meaning, reciprocal contribution, and commitment interact through feedback, and how coordination degrades when these relations are replaced by control. It explains why trust and goodwill tend to emerge from cooperation rather than cause it, why identity systems can destabilise coordination even without malicious intent, and why control becomes dominant when feedback breaks down.

The framework does not tell anyone what to do. It does not propose governance models or institutional reforms. Its purpose is analytic: to make visible the structural conditions that systems already depend on, and the predictable ways those conditions fail.

I study the structures of cooperation that people live inside but rarely see.

My hope is that by making these structures visible, it becomes easier to recognise when cooperation is degrading and when control is being asked to substitute for conditions it cannot replace.

That visibility does not guarantee better systems. But without it, systems tend to repeat the same failures, at increasing cost.